Fermat’s Little Theorem

In number theory, some of the most powerful results are also the simplest to state. Fermat’s Little Theorem is one such result. First written down in the 17th century by Pierre de Fermat, the theorem connects prime numbers, modular arithmetic, and exponentiation in quite an elegant way. This theorem has played a central role in modern mathematics, including cryptography, computer science, and math contests.

Statement of the Theorem

Fermat’s Little Theorem states:

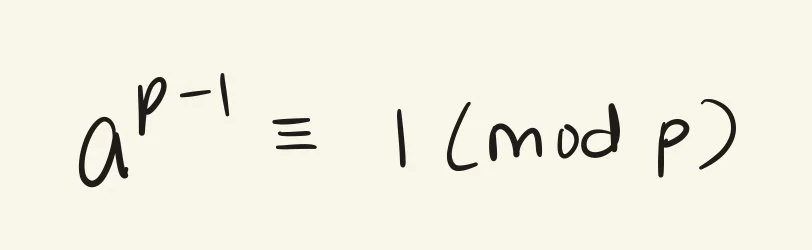

If p is a prime number and a is an integer not divisible by p, then

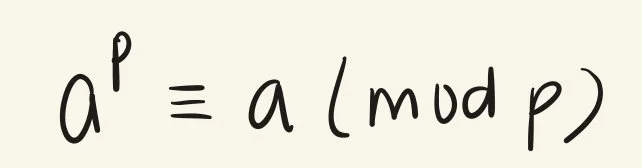

An equivalent and often more convenient form is (simply multiply both sides of the congruence by a):

For any integer a and prime p,

Both versions describe how powers behave when reduced modulo a prime.

Understanding the Meaning

The notation ≡ (mod p) means that two numbers leave the same remainder when divided by p.

The theorem tells us that raising a number to the p-th power does not change its remainder mod p (when p is prime).

In other words, primes impose a special structure on modular arithmetic that does not generally exist for composite numbers.

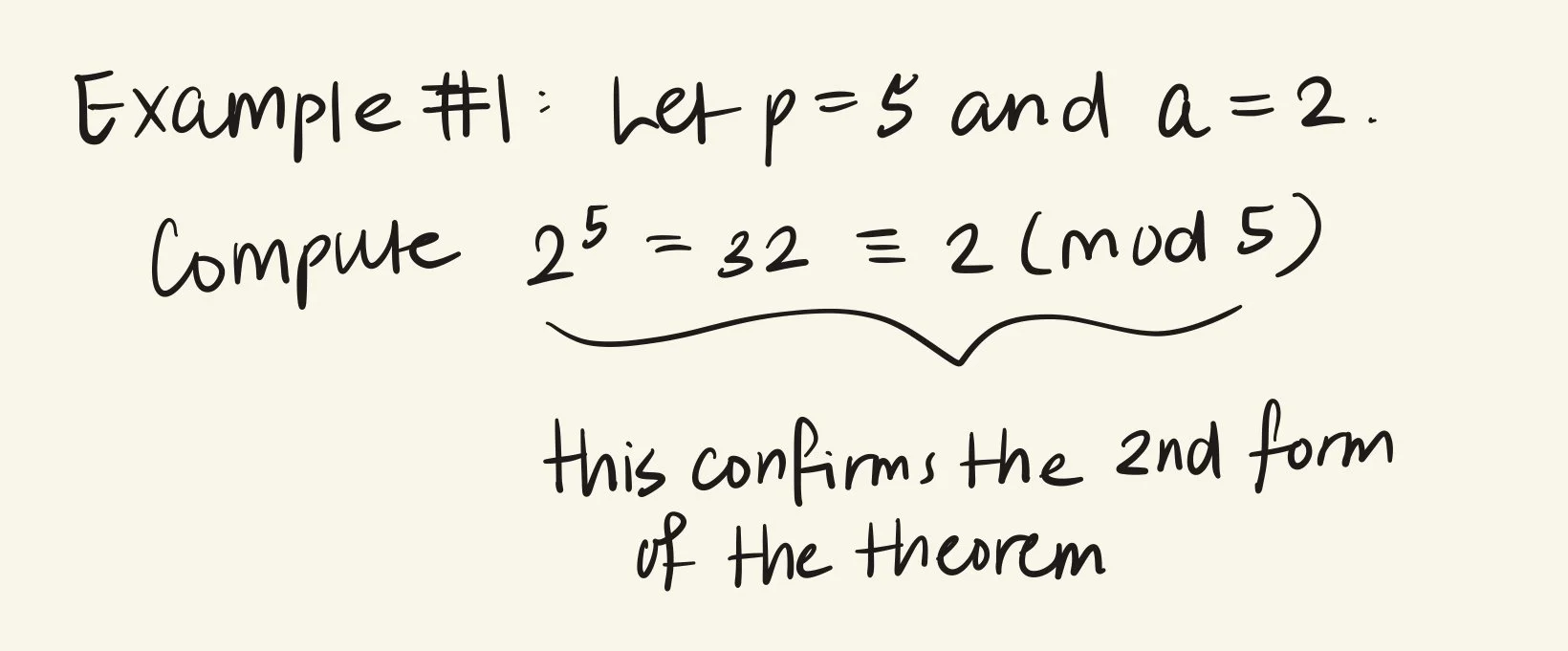

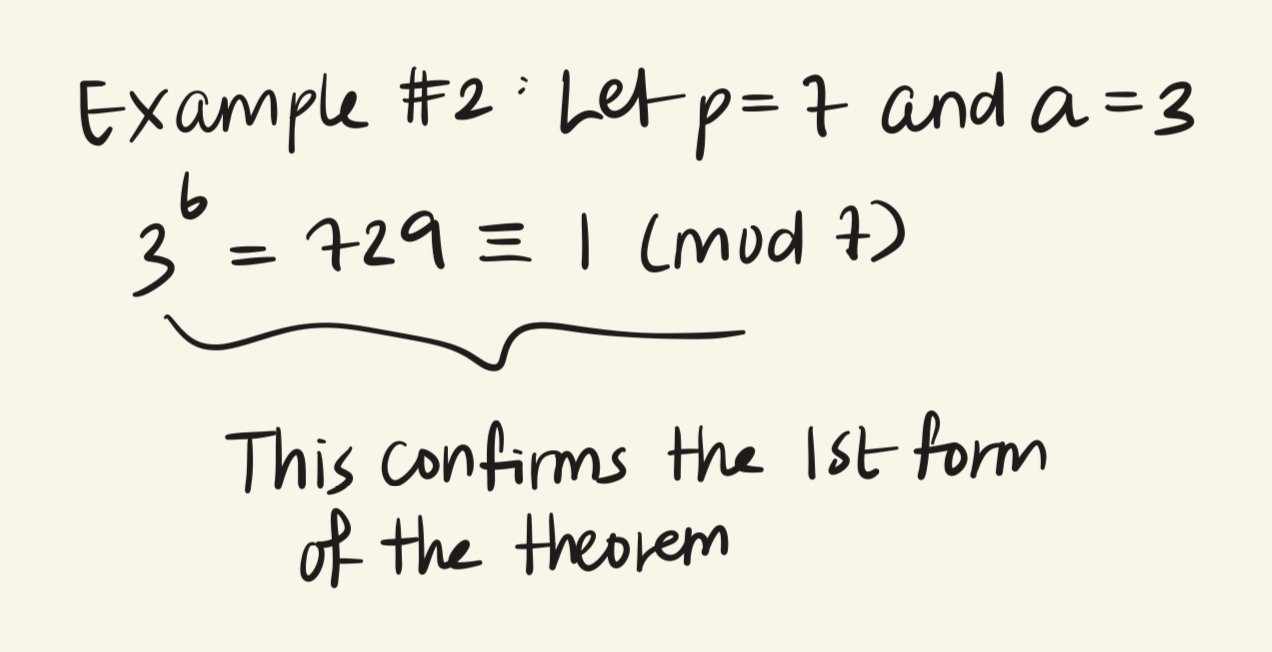

Here are some simple examples:

Why Primes Matter

The key reason Fermat’s Little Theorem works is that, modulo a prime p, every nonzero number has a multiplicative inverse. This allows the nonzero integers modulo p to form a structured system where multiplication behaves predictably.

When multiplying the numbers 1,2,3,…,p−1 by a modulo p, the set of remainders is simply rearranged. This permutation idea lies at the heart of many proofs of the theorem.

Fermat’s Proof:

Step 1: Look at the nonzero residues mod p

Consider the set

S={1,2,3,…,p−1}

Step 2: Multiply everything by a (mod p)

Form the new set

aS={a⋅1, a⋅2, …, a⋅(p−1)} (mod p)

Step 3: Show aS is just a rearrangement of S

We claim all the numbers a,2a,…,(p−1)a are distinct mod p.

Suppose ia≡ja (mod p)

Then p ∣ a(i−j). Since p is prime and p∤a, it must be that p ∣ (i−j).

But i,j∈{1,…,p−1}, so ∣i−j∣<p, which forces i−j=0, hence i=j.

So aS contains each nonzero residue exactly once - just in a different order.

Step 4: Multiply all elements in each set

Multiply the elements of S:

1⋅2⋅3⋯(p−1)=(p−1)!

Multiply the elements of aS (in integers) and reduce mod p:

(a⋅1)(a⋅2)⋯(a⋅(p−1))=a^(p−1) * (p−1)!

But because aS is a rearrangement of S modulo p, the product of its elements is congruent to the product of the elements of S:

a^(p−1) * (p−1)! ≡ (p−1)! (mod p)

Step 5: Cancel (p−1)!(p-1)!(p−1)! modulo ppp

Since p is prime, none of 1,2,…,p−1 is divisible by p, so (p−1)! ≢ 0(mod p).

That means (p−1)! has a multiplicative inverse modulo p, so we can cancel it:

a^(p-1) ≡ 1 (mod p).